Capes, Cowls & Costumes 6: Non-Comic Book Novels by Comic Book Writers

Another installment of the column I wrote for Bookgasm.con in 2008:

Books with no pictures in them? What would comic book writers know about those?

More than you might think, at least in the last quarter century or so. Sure, there’s always been the occasional comic book writer who broke out of the funny book ghetto and made the move to writing prose (Mickey Spillane, William Woolfolk, Gardner Fox, Alvin Schwartz, to name a few off the top of my head), but for the most part, comic book writers stuck with the medium what brung ‘em. If they did write prose, it was likely to be a novelization or adaptation of some comic book or other media property.

These days those boundaries have pretty much disappeared. Successful novelists such as Greg Rucka, Brad Meltzer and Jodi Picoult routinely make the switch between prose and comics. And, comic book writers such as Neil Gaiman and Warren Ellis are doing work that gets them shelved in the Literature section instead of Graphic Novels or Science Fiction. With the advent of respectability for the art form (the New York Times says we’re art, so there!), comic book writers are finally being taken seriously as writers.

Steve Englehart hit comics like a bombshell in 1972 with his runs on The Avengers and Doctor Strange. Forget Vertigo, Steve’s work was a mind-expanding revelation a dozen years before Swamp Thing or Sandman. His stories were at the same time human and cosmic, his characters never getting lost in the often epic sweep of his storylines. Steve Englehart wrote The Point Man in 1981. Set in San Francisco, it is the story of Max August, known to his radio audience as Barnaby Wilde, a popular radio d.j. on a struggling AM station. Life as Max/Barnaby knows it is about to change when, first, a carved lion is stolen from his apartment and, second, people start trying to kill him.

Englehart weaves a rollercoaster ride of music, magic and madness involving the U.S.S.R., the KGB, the FBI, E.S.P., the CIA, radio station KQBU and all the rest of the letters of the alphabet as Max, possessor himself of heretofore unknown powers, helps thwart a plot to destroy the United States through sorcery in a Cold War U.S./U.S.S.R. Magic Gap. Steve’s writing is solid and compelling, evidencing all the skill of a craftsman who has spent the last decade learning how to build an episodic story in the “To Be Continued” environs of comic books yet never giving in to cartoony excess. Sometimes, when comic book writers write prose we miss the luxury of the pictures to help carry our story along. In The Point Man, Steve Englehart never lets the absence of pictures slow his story. It’s a shame he hasn’t written more prose since.

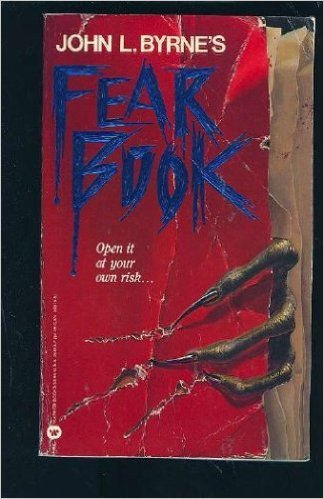

John Byrne was another creator to take comics by storm. After an apprenticeship at the now defunct Charlton Comics in 1975, John began to make his mark at Marvel Comics, eventually taking over as artist on The X-Men in 1977. John, who considers himself a writer first, began scripting his stories in earnest in 1981 when he took over The Fantastic Four. He has since written and or drawn (or both) every iconic character in comics, from Superman to Star Trek. In 1988, John tried his hands at a novel. The result was Fear Book.

While Byrne has frequency displayed his proficiency with the horror genre in comics (most notably in his early-2000s run on Jack Kirby’s The Demon), Fear Book is him playing in the Big Boy horror sandbox. Sam and Joanne Dennison are new arrivals in the town of Fairharbour, Connecticut (a thinly disguised Fairfield, the author’s hometown at the time) when they receive The Catalog in the mail. The horrors it contains and the desires it unleashes in everyone who opens its deep red cover will make the streets of Fairharbour run red with blood. “There, on those painfully white pages. The rages. The anger. The hatred. Buried all those years. Buried. The eagerness to kill and maim and destroy.” Suddenly, Sharper Image doesn’t seem so bad, does it? John followed up his 1988 Horror Writers of American’s Bram Stoker Award nominee for Best First Novel with Whipping Boy (1992) and Wonder Woman: Gods and Goddesses (1997).

Another revelatory comics creator who turned to prose was Jim Starlin who, like Byrne, got his start as an artist before making the leap to write his own material. Known for his own take on the cosmic storyline, Starlin earned well-deserved acclaim for Marvel’s Captain Marvel, Adam Warlock and Shang-Chi and DC’s Cosmic Odyssey, Starlin’s ability to filter a story of Cosmic Significance through his point of view character was well-honed by the time he wrote, with his wife Daina Graziunas, Among Madmen (featuring 50 illustrations and a cover by Starlin).

When the world starts going insane and people turn into savage berserkers for reasons yet unknown (viral? chemical? accident? intentional?), ex-Vietnam vet/N.Y.P.D. cop Tom Laker took his wife into the hills and found refuge in Shandakan, a small town in the Catskill Mountains where, as chief of police, he helps keep the madness at bay. There are several flaws in this plan, including his wife, Maria, who is part time-crazy and murderous herself. Starlin and Graziunas pull off a solid, post-Apocalyptic science fiction adventure tale, grounded by mostly well-realized characters and Starlin’s familiar macho stylings. And the pictures are darned nice, too! The duo have since published Lady El (1992) and Thinning the Predators (1996).

Speaking of familiar territory, I come to Warren Ellis’s 2007 debut novel, Crooked Little Vein. Once again, it’s a ground-breaking comics scripter who makes the leap to novelist. With his rise to fame at DC/Wildstorm on Transmetropolitan, The Authority, and Planetary after a few years toiling in the vineyards of Britain’s 2000 AD and at Marvel, the British writer largely peeled off from mainstream comics to create a host of self-owned titles for Avatar and other smaller comic lines. His work is popular and often controversial. It is often, however, a lot of the same: The Individualist once scorned by the Establishment, now needed by that very same Establishment to clean up their life-as-we-know-it ending messes, mixed with a healthy dose of absurdity and metaphysical double-talk.

Crooked Little Vein is an entertaining romp featuring burnt-out P.I. and shit-magnet Michael McGill is hired by the president’s heroin addicted Chief of Staff to locate and retrieve the lost Secret Constitution, a back-up document crafted by the Founding Fathers to be used only in the case of emergencies. Which is, of course, now. McGill and his Ellisesque-smartass second banana/girlfriend trip off down the Yellow Brick Road of a thin magical realism storyline hung with poorly-drawn caricatures, crazed sex-addicts, unspeakable drug use, improbabilities aplenty, and crazed situations that seem forced and trying too hard to mean something. It seems a bit absurd to do an absurdist thriller. But then, maybe that was the point.

When I worked at Dell in the late 1970s/early 1980s, Englehart's editor on The Point Man gave me a copy of the manuscript and asked for my feedback. I told him that I thought it was a bit too dense -- that he actually had about two or three novels in there. Which was kind of a compliment, but probably not in a way Steve would have appreciated. Anyway, I don't know if that editor gave any weight to what I said, and I don't think I've ever seen a copy of the finished novel.